Marian Smith’s mentors told her not to write her book.

She wrote it anyway.

By Walter Neary

This article is a fuller version of an article in the winter 2023 issue of the Historic Fort Steilacoom newsletter. Comments most welcome.

Marian Smith was an anthropologist who interviewed several elders of the Puyallup and Nisqually Tribes in the late 1930s. Her book, “The Puyallup-Nisqually,” Columbia Press, New York, 1940, has been cited in many ways, from the histories of Nisqually historian Cecilia Carpenter to the new mini-museum created by the Puyallup Tribe. Smith described herself as the last student of a giant of American anthropology, Franz Boas, of Columbia University in New York. By the end of his career, Boas and his disciples had learned that much of the Native American lore they sought to catalog had been lost to time.

There is one sentence in that book that has not aged well. And some might find it offensive: “Puyallup-Nisqually culture is gone.”

This article is about Smith, her work in relation to the Tribes and our fort – and a possible explanation for such a strange thing to say. I call it a strange thing to say, because after that sentence, the book goes on for more than 300 pages to detail Smith’s perceptions of Tribal culture.

I recently visited Smith’s papers and personal archive in London. Why are they London, you ask? Columbia University did not treat women scholars well in the 1940s, so she did not stay there after a brief stint as a teacher. Smith married an Englishman, moved, and would later become one of the key movers of the Royal Anthropological institute, which remains a vital institution today.

I learned with sadness that Smith had saved very few of her papers from her days among the Puyallup and Nisqually. Most of the papers related to the Pacific Northwest were from a trip with students to British Columbia natives that she led late in the 1940s. But she did save a few papers from her undergraduate research days, and I nearly fell out of my chair when I saw it. I’d like to speculate about why she saved it, as I think the letter is also very important to explaining the controversial sentence above.

Smith arrived as a young undergrad in Puget Sound in 1936. She had the use of one leg; function in the other leg was lost to polio. She must have written about what she found to Boas, and/or his chief disciple, Columbia Professor Ruth Benedict. It’s on my list to see if that letter survives somewhere at Columbia. In the meantime, we know how Boas and Benedict reacted.

I found a few notes from her 1936 days. In one, she describes how all the Tribal doctors were dead, or so she had been told. She must have suggested that she thought many memories had been lost. Because Benedict wrote back an eye-popping letter.

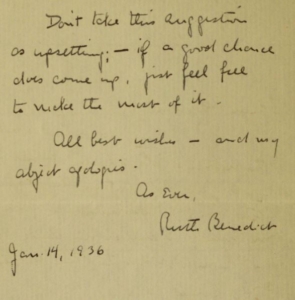

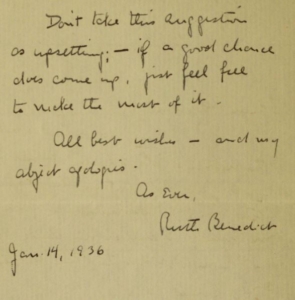

In her letter Benedict very gently suggested that Smith should maybe forget the Puyallup and Nisqually and find other Tribes. Benedict had conferred with Boas. She wrote, “Don’t take this suggestion as upsetting. If a good chance does come up, just feel free to make the most of it.”

The scholar who would later edit the book “The Puyallup-Nisqually”

wrote Marian Smith to suggest switching her focus to another tribe.

Boas at this point was a giant of scholarship, so it would have to be intimidating for him to suggest to his youngest student that she reconsider her project

And yet. Marian Smith published “The Puyallup-Nisqually” in 1940. The two greatest figures of American anthropology at the time had suggested she find another topic. She chose not to do so.

Let’s return to how the book begins with that “Puyallup-Nisqually culture is gone.” Well. That’s that then?

I hope to begin a conversation by suggesting two explanations for that sentence.

One is that she personally felt that way. Columbia’s scholars spent a lot of time with a lot of Tribes in ways now thought controversial and problematic.

Here’s another option: Maybe it took the entire cultural arrogance of the Columbia University Anthropology department to put its weight behind that statement. Here’s something I probably should have told you earlier: the book was edited by Ruth Benedict.

As Boas’ career was drawing to a close, he was growing concerned that many of the recollections they cataloged were compromised. It was known that some Natives, for profoundly understandable reasons, did not want to share private recollections with a white stranger, and certainly not one who represented the full weight of the white academic system. This happened with tribe after tribe. By the end of his career, Boas knew that he and his students had collected falsehoods mixed with valuable information.

The paragraph that began with that sentence offers important context. It continues, “If the old life has come alive again and to me it certainly seems most vivid, it is due to the real and intelligent interest of my informants, especially of Jerry Meeker, John Milcane, William Wilton and Peter Kalama. They offered their memories, their hospitality, and their friendship, and this book is a monument to the culture into which they were born and which they saw vanish before their eyes.”

At the end of this paragraph, the reader is properly muddled.

What is in this paragraph?

- The culture is gone

- It has come alive again

- It has vanished

When Smith went to British Columbia in the late 1940s, she apparently stopped by Puget Sound to visit the Kalama family. Or maybe the pictures in her album are from her earlier days. Either way, her interested in these people seems very sincere.

So to sum up: We just don’t know the origins of the sentence. But we do know some of the reaction. A paper written by a doctoral student at the University of Washington addresses “culture is gone.” Karen Marie Capuder wrote in 2013,

“It is undoubtedly true, as will be recounted throughout this dissertation, that incredible and often devastating changes had been wrought in peoples’ lives throughout Puget Sound due to the active efforts of federal and Christian assimilationists to destroy First Peoples’ systems of governance, spiritual praxis and land tenure, as well as their languages, subsistence strategies and sacred responsibilities within their sentient homelands. It is not entirely true, however, to say that “Puyallup-Nisqually culture is gone.”

Very fortunately, there is more to the work than that sentence. Any interchange with a Tribal member was precious in the late 1930s and offered vital information, whatever “scholars’ at Columbia University wanted to judge about it. Capuder notes in her dissertation that Smith gathered important materials still of use today.

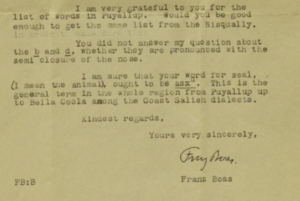

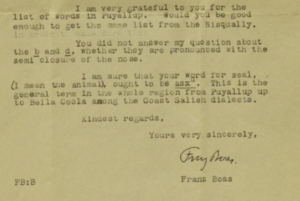

Six months later, Columbia’s giant of anthropology, Franz Boas, must have eventually approved of Smith’s choice as he thanked her in this letter for information.

For example, the new Puyallup Tribe museum quotes one of the most disturbing passages in her book in one of ther displays. Smith wrote that people in Tacoma had learned that if you wanted to get land from a Native, you could arrange to have them hit and killed by a train so that it looked like an accident. Even though Smith was an anthropologist, she wrote this about present times. Surely that was a deliberate decision on her part to include a present-day detail.

For those of us who dive deep into the history of Fort Steilacoom, Smith also quotes elders who were the grandchildren of the Natives who were part of the Fort community – and part of the Puget Sound Treaty War – in the 1850s.

Smith actually published very few political feelings of the Elders. Her main interests, driven by the Columbia approach, were the nuts and bolts of daily life: matters like clothing, spiritual beliefs, methods of giving birth and raising children. As part of that, Smith did ask about how Natives had conducted war. And that led her to a passage about the Treaty War that is most interesting. It reminds us of the writings of Fort Vancouver’s commander, who wrote in a letter home that it was terrifying how Puget Sound Natives outnumbered Army soldiers here in the 1850s. Smith’s account of the death of Lt. William Slaughter is different than you’ll find in most accounts.

“With the cooperation of the Sahaptin relatives, a group of inland Salish sent out scouts to follow and spy upon a detachment of soldiers sent to the foothills to capture Leschi. The soldiers encamped above a stream at the head of a gully while two scouts watched their preparations from separate vantage points. Finally, a soldier moved away from the group toward the creek and toward one of the scouts. As he bent to fill his water pail, the scout rose from his hiding place, fired and killed the soldier. Not to be outdone, the other scout fired upon a second soldier who stood near the edge of the encampment”

“The camp was aroused, the scouts fled, the Indian party waiting for the attack dispersed and the soldiers were saved from a situation in which they would most certainly have been at a decided disadvantage. The fatalities were among the very few suffered by the military during the trouble. The two Indians who inflicted them were looked upon as brave men and their fame stood out strongly in comparison to the lack of similar accomplishment by others.”

This passage invites us to contemplate a version of the Treaty War that could have been much more bloody.

In summary, we can be glad Marian Smith did not heed the gentle coaching of her mentors. We can be glad she interviewed and published recollections.

And while I have no direct evidence of this: Perhaps she held on to Benedict’s letter perhaps as a reminder of a crucial, hard decision that a young vulnerable student had to make to create arguably her most important contribution to scholarship.

Author’s note: I thank the archivists and staff of The Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland in London for their assistance in research. If you’d like to know more about Marian Smith, you might start with this Wikipedia page. Then I recommend using search engines to find the various obituaries published after her death.