What Your Parents Knew About Local History Was Likely Wrong

By Walter Neary

Across the nation, many museums honor the U.S. Army while grappling with the challenging history of westward expansion. However, Fort Steilacoom Museum didn’t emerge until 1980. Even now, more than 40 years later, many people say they have never heard of Fort Steilacoom.

Why Did Fort Steilacoom Disappear from Public Memory?

The answer lies in how history gets remembered — and sometimes rewritten. For decades, efforts to honor American pioneers focused elsewhere, leading to the erasure of Fort Steilacoom. Generations were taught that another fort, seen as truly American, had already filled this role. So when we ask people to recognize Fort Steilacoom as the American fort, we are erasing what their parents may have taught them. We are asking people to un-learn.

I should add here that this article is deeply in debt to historian Steve Anderson, who wrote this year about how Fort Nisqually came to dominate the pioneer narrative.

A Shift in Focus: Fort Nisqually as the “American” Fort

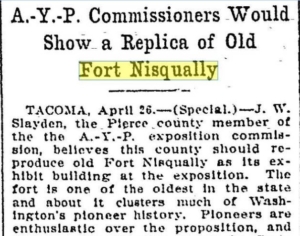

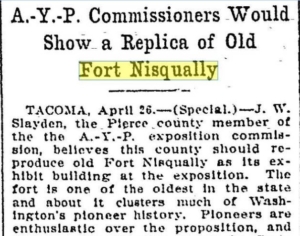

By 1908, papers like the Seattle Post-Intelligencer were advocating for a replica of Fort Nisqually to be built for the Alaska-Yukon Exposition. This idea never took off, but it showed that Fort Nisqually was seen as central to Washington’s pioneer history.

It is worth noting that Fort Nisqually, located in DuPont, was actually a British fort. But two key events helped elevate its prominence:

- Historian William Bonney declared that Fort Nisqually’s factor’s house was the oldest building around — the first white settlement. This blurred the line between British and American history. British. American. White. All the same thing, right?

- With the rise of the automobile, the scenic drive from Seattle and Tacoma to DuPont made visiting the old fort a popular outing.

The Rise of Fort Nisqually in the Public Eye

By 1921, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer was calling Fort Nisqually “the site of the first American home built in the Puget Sound District.” The Tacoma Daily Ledger went even further, dubbing it “the cradle of American civilization in the Pacific Northwest.”

Visiting the site became a trend. It became quite a thing to visit the old buildings at their original rustic site in DuPont, as is shown in this front page display in the Oct. 30, 1927 issue of the Tacoma Daily Ledger:

But while Fort Nisqually thrived in the public imagination, Fort Steilacoom, now part of Western State Hospital, was left in the shadows. Few ventured out for scenic drives to an asylum, and the stigma surrounding the hospital only added to the fort’s fading presence. The wording that one newspaper writer used in 1950 is significant in how direct it is: “Fort Steilacoom became Western State Hospital.”

A group of young Tacoma businessmen donned costumes appropriate for a John Wayne movie and pretended to take hostages among American pioneers, just like what NEVER happened at Fort Nisqually. Photo Source of this and the adjacent photo, Tacoma Northwest Room

“Red men” so wrong in so many ways

In the public imagination, there was no need for Fort Steilacoom because Fort Nisqually had been re-created in Point Defiance Park in 1934. The dedication ceremony for the replica fort was quite the spectacle, with a band playing patriotic tunes, U.S. Navy planes performing stunts, and the American flag raised as onlookers stood at attention.

The Americanization of Fort Nisqually, a British fort, was misleading. It got worse. In one wildly inaccurate and offensive moment, actors dressed as “red men” reenacted an imaginary hostage-taking of settlers — an event that never happened at Fort Nisqually.

But you can’t blame people for thinking that. The Tacoma Daily Ledger had called Fort Nisqually “the old fort that once protected the settlers of Pierce County from attacks by raiding Indians.”

Forgive me this tangent: So how did these non-existent American hostages from a non-existent fort get rescued? “A company of (US) national guardsmen scheduled to appear on the scene and rescue the officials failed to show and it fell the duty of a German band supplied by the Veterans of Foreign Wars. Tacoma police and state patrolmen to repulse the attack and return the officials to safety.”

An American flag is displayed during the Fort Nisqually dedication, just as it never was during actual history.

So it’s no wonder nobody in Tacoma or Lakewood ever heard of Fort Steilacoom. It didn’t exist. Newspapers, such as the Seattle Daily Tribune of June 11, 1939, refer to Fort Nisqually as part of “the history of US military defense” in Puget Sound

A Stamp Seals the Confusion

With Fort Nisqually celebrated as a symbol of American pioneers, Fort Steilacoom was forgotten. Forty-four years later, the U.S. Postal Service embraced historical inaccuracy.

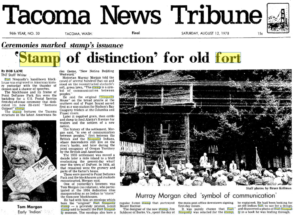

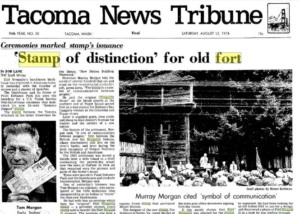

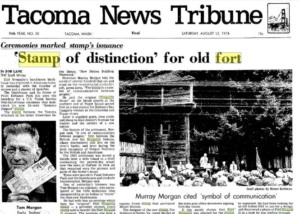

In 1978, the Postal Service issued a stamp called “New Nation Building Westward,” which featured Fort Nisqually’s tower (You can see the stamp in the upper left of this page). The stamp was interpreted as celebrating U.S. settlement, despite Fort Nisqually being a British outpost.

The ‘red men’ travesty shows up again 44 years later

Just to help emphasize the inaccuracy, guess who showed up for the First Day of Issue ceremony? One of the “red men” from 1934 who you can see in the lower left of The News Tribune front page below. He could repeat the story of hostage-taking for anyone who missed it in 1934.

British fort? American fort? No difference really, in 1978 – which, at least for some of us, seems like modern times.

British fort? American fort? No difference really, in 1978 – which, at least for some of us, seems like modern times.

It’s easy for us today to look back in disbelief. Here in 2024, we know there’s a clear distinction between Great Britain and the United States.

And yet, we should not be smug.

If you had been there in 1934 – if you had been there in 1978 – would you have stood up and said, “Excuse me, excuse me; we’re in the wrong place. We need to take this event to the grounds of the mental hospital! Who is ready to drive to Western State Hospital and have a big public party?”

Most of us probably would not have done that. It’s just easier to go along for the ride.

Bringing Fort Steilacoom Back into Focus

Thanks to Lakewood historians Cy and Rita Happy, who nominated Fort Steilacoom for the National Register of Historic Places in 1976, the fort’s story is being preserved. Volunteers restored the remaining buildings in the 1980s, and since then, our association has worked to share the history of the fort, its people and the stories of those around it.

But we’re asking people to unlearn something they’ve been taught. And that’s often harder than teaching something new.

Why Does This Matter?

Does it matter whether Puget Sound remembers the U.S. Army’s role in Washington’s history? Does it matter that Fort Steilacoom exists as a museum?

Museums across the country, many with significant resources, are beginning to tell the fuller stories of Native Americans, colonialism, and westward expansion. Sites like Fort Vancouver, the Whitman Mission, and Little Bighorn Battlefield are working to include all sides of these narratives.

All-volunteer Fort Steilacoom, with just a fraction of the budget of publicly sponsored museums, faces challenges in doing the same. Nobody wants the bureaucracy that comes with a big museum, but there’s something to be said for expertise and budget.

Fort Nisqually: A Remarkable Legacy

Despite all this confusion, something wonderful did come out of these missteps. Thanks to the passion for preserving U.S. history, we now have an incredible British fort in our midst. Fort Nisqually is an outstanding museum that tells the story of its British roots, and we’re fortunate to have it.

Fort Nisqually is a remarkable museum in any ways, and it’s hard to imagine the history community in the South Sound without it. Their volunteers bring enormous life and energy and expertise when they visit Fort Steilacoom.

Fort Nisqually is blessed with wonderful staff and volunteers and programs. And it’s an example of what a professional museum can do.

It was Fort Nisqually and its parent, MetroParks Tacoma, that organized a podcast series that embraces the stories and perspectives of Native Americans in Puget Sound. During Fort Nisqually’s Candlelight Tour, they feature an American camp outside the fort. This camp includes re-enactors portraying American soldiers and settlers who share their hopes and dreams for the 1850s.

While Fort Steilacoom seeks to tell its story with limited resources, we have exciting plans for the future. Stay tuned for updates on how we’re working to expand the fort’s reach.

British fort? American fort? No difference really, in 1978 – which, at least for some of us, seems like modern times.

British fort? American fort? No difference really, in 1978 – which, at least for some of us, seems like modern times. With Fort Nisqually celebrated as a symbol of American pioneers, Fort Steilacoom was forgotten. Even the U.S. Postal Service contributed to the confusion. In 1978, it issued a stamp called “New Nation Building Westward,” which featured Fort Nisqually’s tower. The stamp was interpreted as celebrating U.S. settlement, despite Fort Nisqually being a British outpost.

With Fort Nisqually celebrated as a symbol of American pioneers, Fort Steilacoom was forgotten. Even the U.S. Postal Service contributed to the confusion. In 1978, it issued a stamp called “New Nation Building Westward,” which featured Fort Nisqually’s tower. The stamp was interpreted as celebrating U.S. settlement, despite Fort Nisqually being a British outpost.